Simply put, secular music is any music that’s not sacred in nature. Secular music isn’t religious or used in worship of any kind; it is used for entertainment rather than religious purposes.

What Is Secular Music

The term secular music is often used to describe music from the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and the periods following. Although we tend to refer to it as classical music in the broader sense, calling non-church music secular music simply means it wasn’t commissioned by the church nor composed for it.

We’ll go on a time-traveling mission to understand the difference between sacred and secular music. Our focus will be on Western or European music.

Examining Secular Music through the Ages

The Middle Ages lasted between 800 and a thousand years between the 5th century CE and 1300, 1400, or even 1500, depending on the region of Europe.

As a side note, historians prefer not to use the term ‘Dark Ages’ because there were, in actual fact, many inventions and discoveries going on during that period.

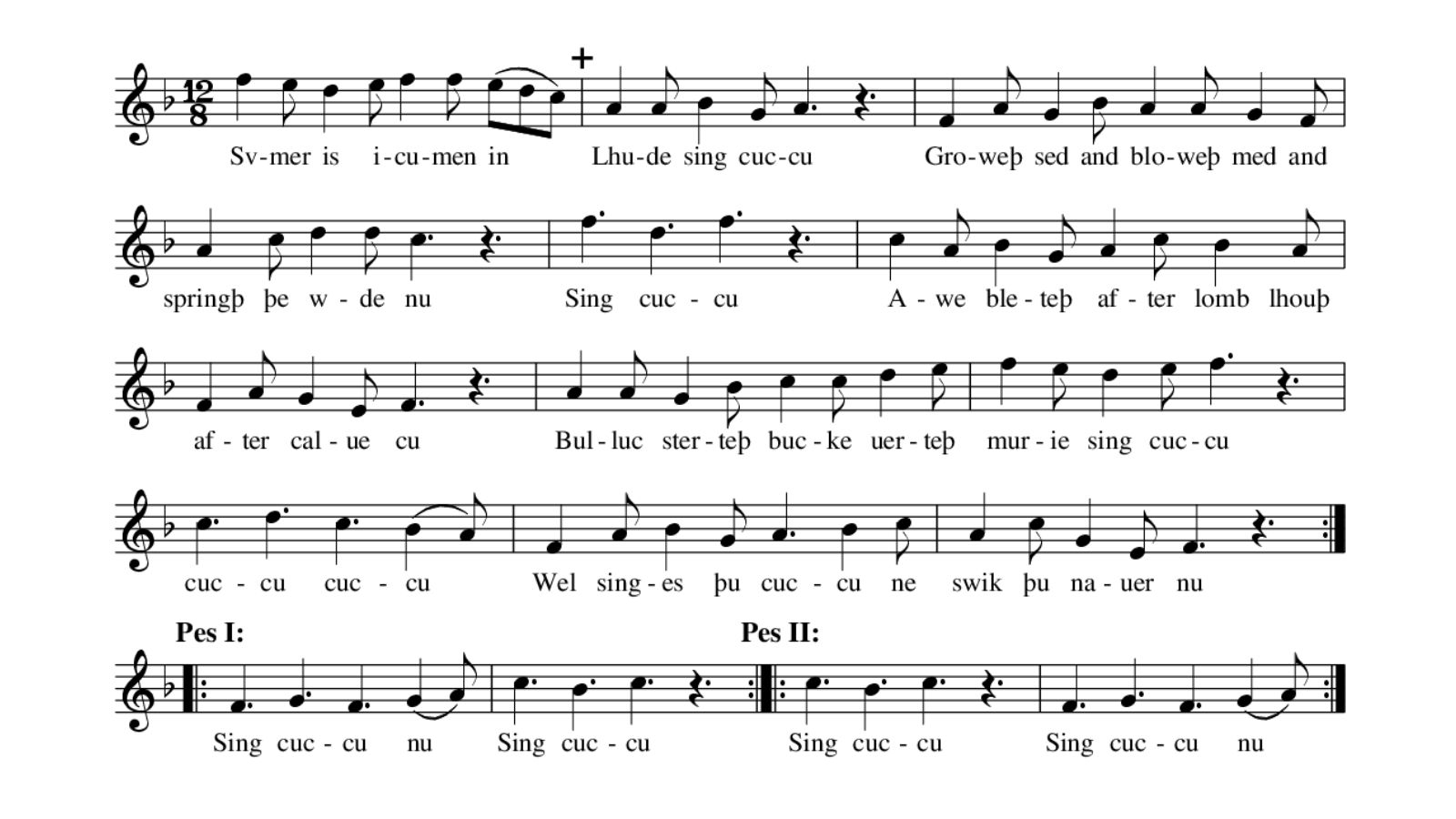

Classical Examples

Our journey starts in 1310 with Summer is Icumen In (Summer is a’coming) composed by an unknown composer, but speculation thinks it could have been W. de Wycombe—a composer and copyist from the medieval period. The composition was most likely copied between 1261 and 1264.

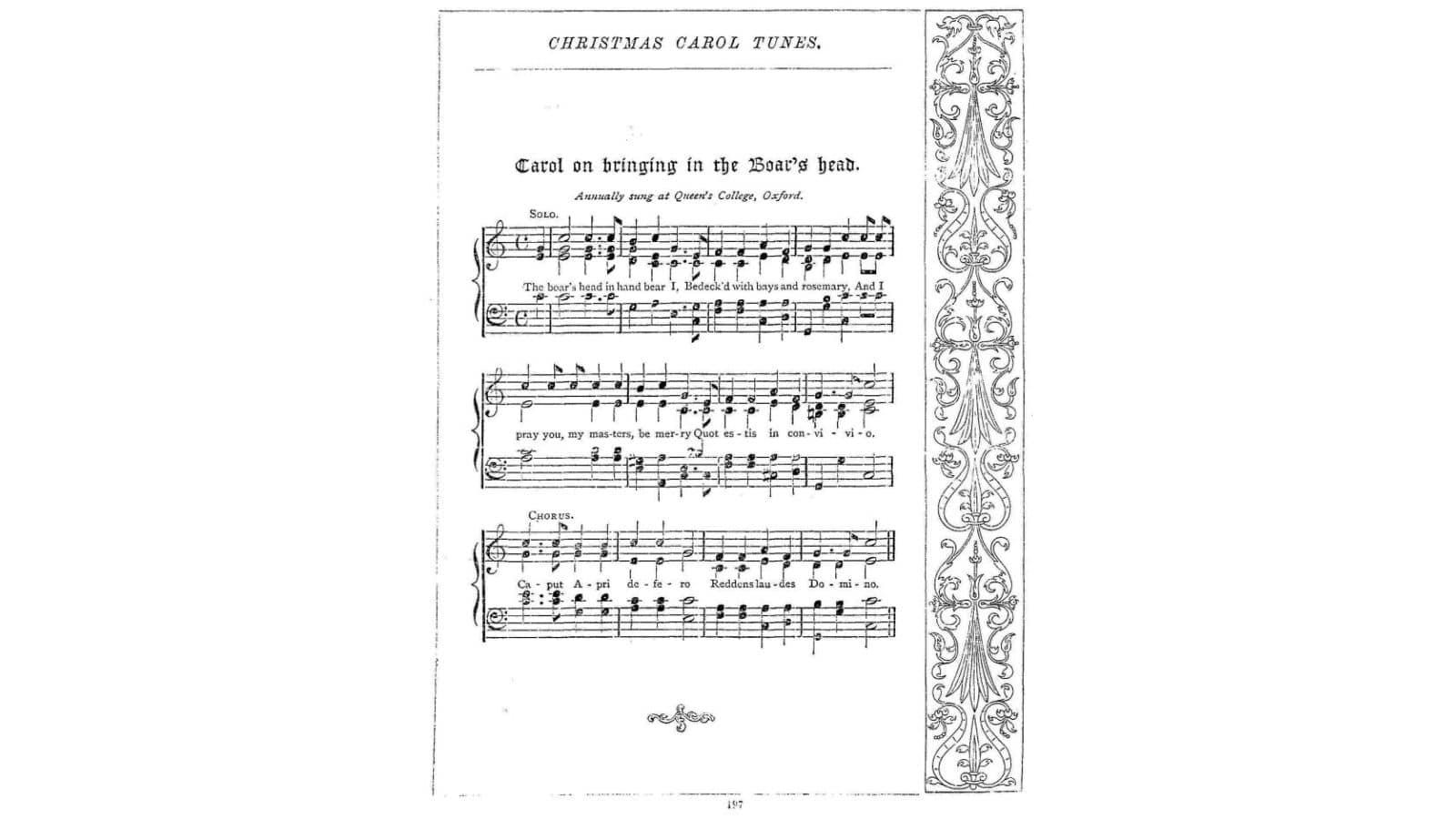

We’re still in England, but the year is 1521 now. The Boar’s Head Carol does not celebrate the birth of Christ but instead paints a vivid picture of a Christmas feast. Instead of being religious, this song focuses on merrymaking, drinking, and eating.

The actual festival referred to in the song is probably a pagan festival that came with the Norse invaders across the ocean, which morphed into Saint Stephen’s feast day.

The song was first published in 1521 by Wynkyn de Worde in England. Still, in all probability, it was around for a while before being published.

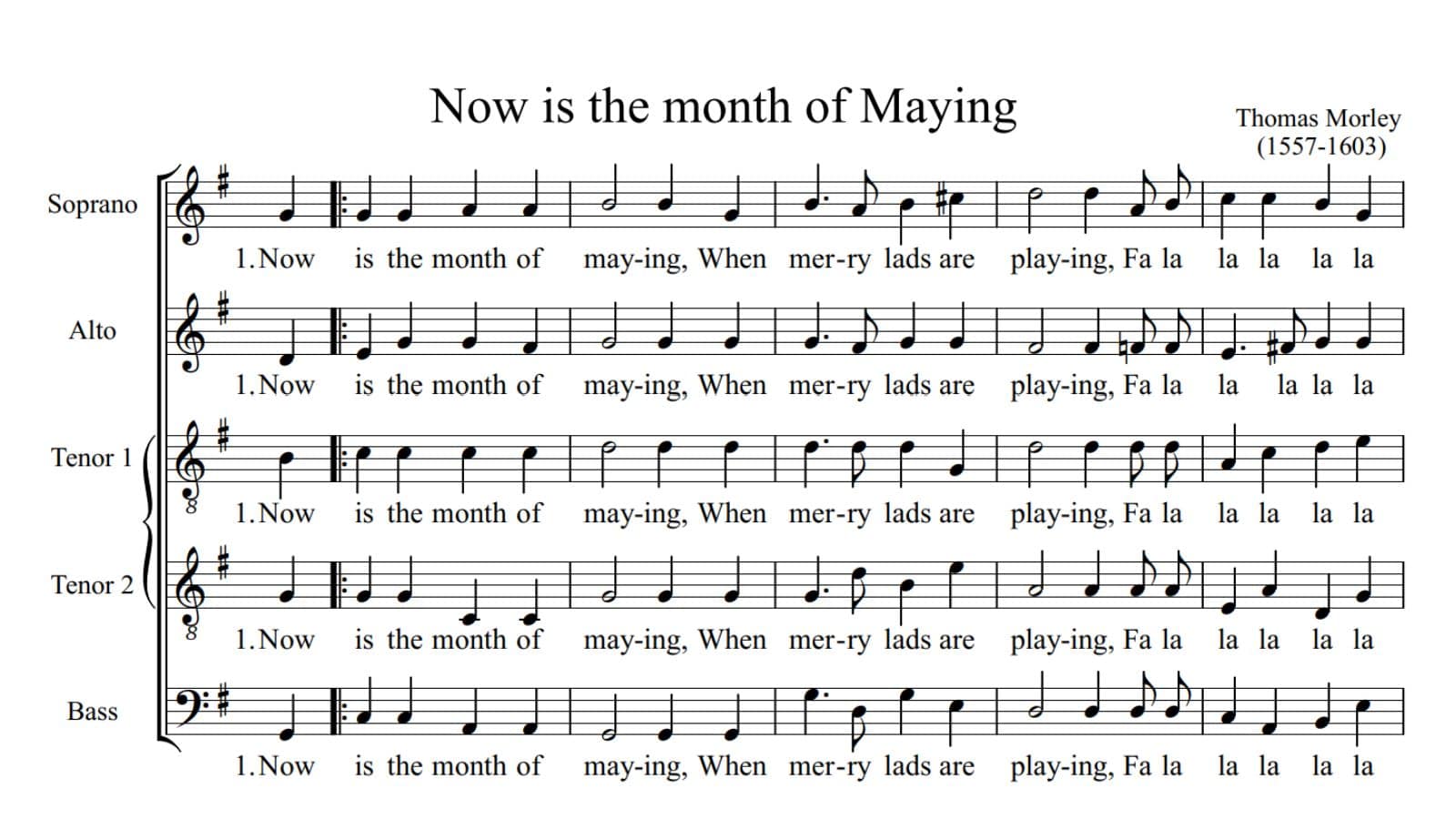

Our last visit to England takes place in 1595. For the record, censorship isn’t a modern invention… In Thomas Morley’s song Now Is the Month of Maying by Thomas Morley, he could not openly refer to romantic love and actions, so he used nonsensical ‘filler’ such as fa-la-la-la-la (first occurrence at 00:24).

This ballette, with its sparkling rhythms and unison singing, creates a dance-like character. The lyrics are also filled with double entendres referring to sexual activities. The madrigal is composed for five voices.

Staying with madrigals, we’re jumping to the European mainland and arriving in Italy. We’re visiting a nobleman musician and composer who composed music for his own enjoyment—Carlos Gesualdo, Prince of Venossa.

Gesualdo is perhaps most famous for the murder of his wife and her lover and is equally renowned for his highly chromatic madrigals.

His madrigal, Moro, lasso, al mio duolo (I shall die miserable in my suffering) from his sixth book of madrigals was published in 1611.

Chromaticism like this would not be seen again until 300 years later in the works of composers like Schoenberg and Stravinsky—talk about being ahead of your own time.

Time for a coffee break, so let’s turn to the master, JS Bach. His secular cantata, Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht, BWV 211 (Be still, stop chattering), is about a troubled daughter trying to convince her father about her dependence on coffee.

Lieschen the daughter’s aria, is perhaps the most recognizable part of the cantata. The work is classed as a cantata but is, in essence, a miniature opera.

Bach is well-known for his profoundly moving religious positions, and his secular works are on par. An interesting fact about Bach is that he also parodied religious and secular works in his own compositions.

Antonín Dvořák’s opera Rusalka (1914) contains one of the most moving arias from the twentieth-century operatic repertoire.

Song to the Moon also inspired another secular hit, Somewhere over the Rainbow, as Judie Garland sang in The Wizard of Oz (1939). Dvořák’s aria is filled with deep emotions as expressed in secular music in the Romantic era.

Contemporary Examples

While many classical compositions are secular, not all secular music is classical. By the early mid-nineteenth century, music started to shift away from the classical idiom, and the jazz era began taking over. Let’s investigate some contemporary examples below.

Scott Joplin (c. 1868—1917) was a ragtime composer, and one of his most famous compositions is The Entertainer. Ragtime is considered one of the influences of jazz, along with several other influences that came together.

My Baby Just Cares for Me is a jazz standard first used in the 1930 musical comedy Whoopee! It also rose to fame when Nina Simone recorded it for her 1958 debut album Little Girl Blue.

Before the internet came in, there were the Beatles. They had a worldwide following on both sides of the Atlantic. While their music wasn’t overtly religious, they used religious imagery in some songs like Lady Madonna. John Lennon said the Beatles were more significant than Jesus.

Moving into the internet age, Carly Ray Jepsen’s song Call me Maybe. Her song took the secular music world by storm and has inspired memes, gifs, and even tweets. The internet age needed a piece, and Carly’s provided just that.

Conclusion

Secular music is perhaps best defined as music that wasn’t composed for religious purposes. Neither secular nor religious music is better than the other; they are just two genres. Both types of music contained elements relevant to the time period it was composed in.

The church’s preference for preserving religious music doesn’t discount secular music as being ‘not worthy.’ Secular music has always been around and is here to stay for us to enjoy.