Female composers have throughout history frequently been overlooked in favour of male composers. The reasons given were usually flimsy, biased and even ignorant.

Whilst female composers are more widely respected and receive proper recognition today, many significant works are not known and are rarely performed.

Below is a small attempt to bring to the wider attention of the listening public some symphonies by a tiny handful of women composers.

Symphonies By Female Composers

Vítězslava Kaprálová (1915-1940) – ‘Military Sinfonietta’ Op.11

Kaprálová was reportedly a child prodigy. Born in what is now the Czech Republic, she began to compose from the age of nine and by the age of fifteen was studying composition at the Brno Conservatory with Vilem Petrzelka.

Her later studies were alongside key figures in musical history including Martinu and Nadia Boulanger.

Kaprálová composed a vast array of works in her short life including many chamber pieces and some substantial orchestral compositions. Dating back to Kaprálová’s study at the Prague Conservatory is the Military Sinfonietta. It was completed in 1937 and is a single-movement work.

As an important point regarding the title of the work Kaprálová says, “The composition does not represent a battle cry, but it depicts the psychological need to defend that which is most sacred to the nation.”

Amy Beach (1865-1944) – Symphony in E Minor, Op. 32, “Gaelic Symphony”

Amy Beach was one of the most influential female composers to herald from the USA. She composed over three-hundred works with the majority of these receiving performances in her lifetime.

Both of these things were remarkable for the time Beach lived in. Beach was a self-taught composer and towards the end of her life put her experiences and principles into a book for budding composers called “Ten Commandments for Young Composers”.

Beach’s husband, Dr Henry Beach, who she married at eighteen, prohibited her from receiving any kind of tuition but did thankfully allow her to publish works under the name Mrs H.H.A Beach.

The Symphony in E minor made history. Beach was the first female composer to receive a performance of a symphony by a major orchestra.

This came in 1896 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The symphony was completed in 1894 and consists of four movements, the outer two marked as fast, the second a siciliana and the third a lento.

The Gaelic in the title stems from Beach’s inspiration that came from Irish, Scottish and English folk melodies.

Florence Price (1887-1953) – Symphony No.4 in D minor

Florence Price was an astonishing artist. By the age of four she was fluently performing at the piano and by the tender age of fourteen had graduated from high school.

Price studied music at the New England Conservatory and holds the credit of being the first African-American female composer to have a symphonic work played by a major orchestra.

Price’s music beautifully absorbed and amplified the European traditional music but more importantly the sounds of urban life and the African-American church.

Dvorak’s music played an important part in her compositional style but Price carved her unique pathway through symphonic music incorporating modernism with the spiritual. Price composed four symphonies.

This final symphony dates from 1945 and the manuscript was discovered in her summer house in 2009. It is a fascinating work formed in four movements. The third movement titled Allegro: Juba illustrates Price’s facility for intertwining musical genres.

Alla Pavlova (1952) – Symphony No.6 (Vincent) 2008

I feel it is important to include living composers among the women listed here. Alla Pavlova is Ukrainian-born but now lives in New York, USA. Pavlova’s output has been copious with a distinct focus on the symphonic. To date, Pavlova has composed eleven symphonies the last in 2021.

The Sixth Symphony marks a harmonic turning point in Pavlova’s music. In this four-movement work, Pavlova moves consciously away from the avant-garde landscape she previously inhabited towards a neo-romanticism.

Listening to this work you could be beguiled into thinking this was Tchaikovsky, such is the orchestration, melody and harmonic content. The symphony was inspired by the famous painting by Vincent Van-Gough, Starry Night, and conveys the dark torment this painter endured.

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944) – The Prison (1930)

Whilst Smyth did not compose a symphony she did complete two symphonic works. She is also one of the most important female figures in musical history and therefore is included here.

Smyth, like other female composers of her time, struggled to pursue a career in music. Her father was a high-ranking military man who did not approve of her aspirations although did allow Smyth to go at around seventeen years old, to the Leipzig Conservatory to study with Carl Reinecke.

Smyth also met Tchaikovsky, Dvorak and Grieg whilst she was at Leipzig but became disenchanted by the poor teaching after only one year. It was Arthur Sullivan who Smyth struck up a friendship with on her return to England and who was a great supporter of her work.

The work of Smyth’s I chose to include here is symphonic in nature and stature. It is an oratorio. Smyth was not a stranger to prison having been incarcerated in Hollow Prison in 1912 for her direct involvement in the suffragette movement.

The work is based on a text by Harry Brewster (a close friend of Smyth’s), from 1891 that folds four perspectives into a discursive narrative in a similar way to Plato.

What we hear is a dialogue between an innocent prisoner, in literal and metaphorical solitary confinement, on the eve of his execution and his soul. The orchestration is stunningly evocative with meticulously constructed melodies reminiscent at times of Elgar and Britten.

Johanna Senfter (1879-1961): Symphony No. 4 in B flat Major, Op. 50

Johanna Senfter was a renowned German composer. She was born in Oppenheim in Germany and died there leaving an enduring legacy in that town.

Senfter was a pupil of Max Reger and the two families were closely attached for many years. Her outpouring of compositions, particularly after Reger’s death in 1916 was astonishing.

Currently, it is believed Senfter wrote over 134 works including nine symphonies, three violin concertos and a large quantity of chamber and choral music.

The Fourth Symphony is a warmly romantic work in four movements. At the first hearing, you could be forgiven for thinking you were listening to Anton von Bruckner or the late Beethoven but Senfter’s voice quickly becomes unmistakable.

The handling of melody, harmony and form stems from the late romantics but Senfter’s symphony draws new life from old ideals. This composition is a testament to her ingenuity.

Libby Larson (1950) – Symphony No.5 (1999); Solo Symphony

Larson is one of America’s most celebrated living composers. She has over 500 compositions to her credit ranging from orchestral to solo songs. Larson is the recipient of a Grammy Award and has more than fifty CDs to her name.

Amongst her catalogue of works are five symphonies, each with a very unique focus. The Fifth Symphony was composed for the Colorado Symphony Orchestra and is structured in four contrasting movements each with an illuminating title.

The opening movement is titled Solo-solos; the second, One Dancer, Many Dances; the third, Once Around, and the fourth The Cocktail Party Effect. Larson explains that the symphony is “about the one and the many”.

Larson’s orchestration is refreshing and well-measured. You will hear echoes of jazz (notably in the woozy trombone solo that opens movement two), and hypnotic dance rhythms often pounded out through the generous percussion section.

I hear the influence of Copland and Bernstein in this composition, especially in the use of the instruments. The fifth symphony is an energetic, dynamic, and compelling introduction to the work of this composer.

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875) – Symphonie No.3 in G minor Op.36

Louise Ferrenc may not be a name you’re familiar with but she was an extremely important composer of her age. French-born, Farrenc composed extensively during her lifetime including three symphonies, choral works and many chamber works.

Farrenc’s Nonet caught the ear of no one less than the legendary violinist Joachim who led the ensemble that gave the premiere.

She was a formidable pianist whose talents were acknowledged by eminent figures such as Clementi and Hummel although her academic studies were hampered due to her sex.

She gained tremendous fame as a pianist eventually securing a permanent professorship at the Paris Conservatory.

This symphony was the last one Farrenc composed. It is formed in four movements. The work contains unsentimental lyricism, and a rigorous strength of structure but always a persuasive dramatic edge.

Ferenc’s music is generous of spirit but equally carefully measured and never gregarious. She presents clarity of line, musical argument and considerable spirit in this symphony that Schubert or Mendelssohn would have been rightly proud of.

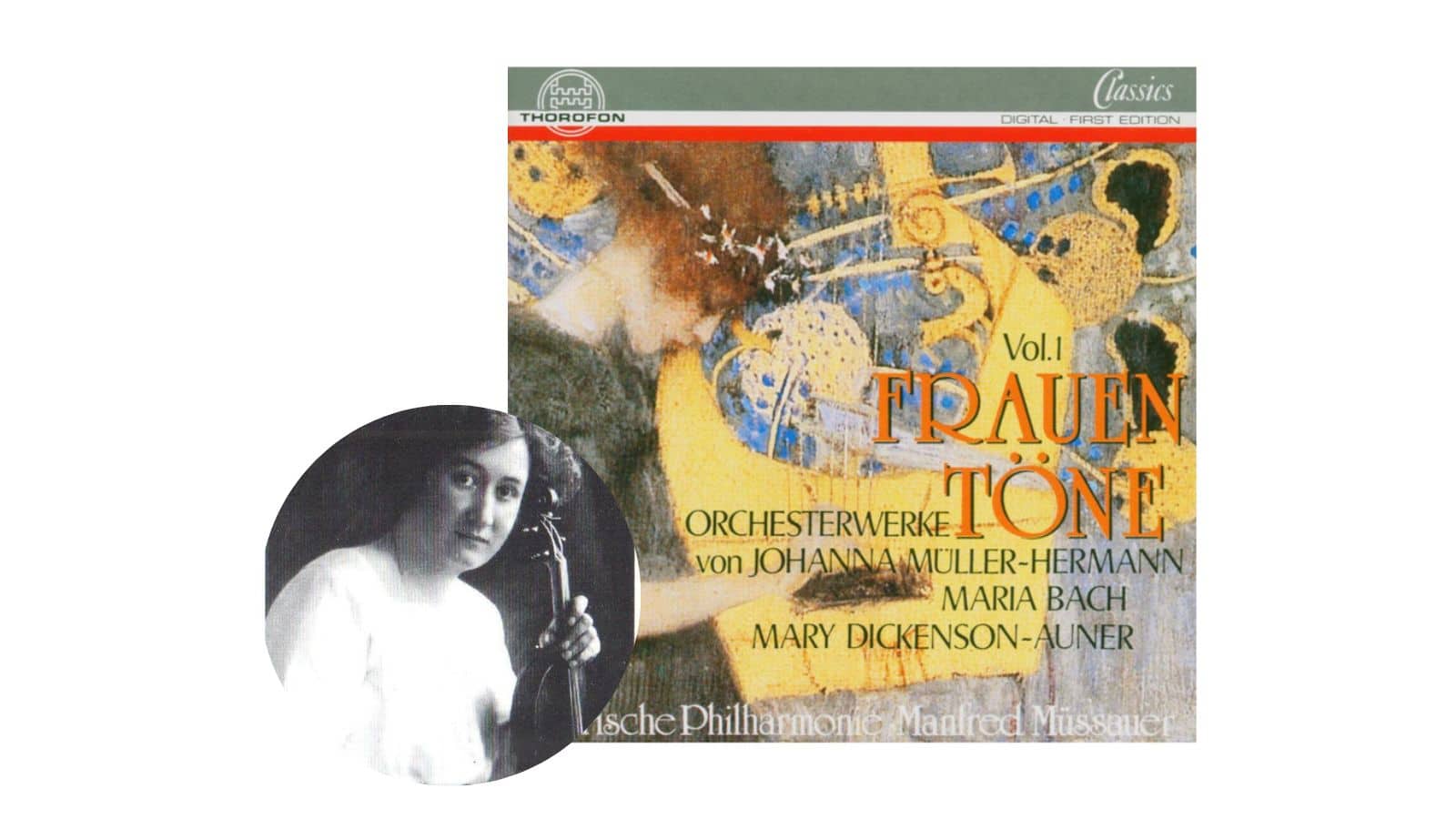

Mary Dickenson-Auner (1880-1965)

Like so many of these outstanding composers, Mary Dickenson-Auner was a brilliant violinist as well as a fine composer. Such was her skill level that she gave the premiere of Béla Bartók’s First Violin Sonata. Dickenson-Auner was also closely connected with Arnold Schoenberg.

She was born in Dublin, Ireland into a family with good connections and reasonable wealth as her father was a doctor.

Having endured the horrors of the Second World War, and moved from Vienna to the Netherlands and back again it wasn’t until Dickenson-Auner was nearly sixty years old that she finally decided to devote her life to composition.

In that period, she composed six symphonies, four operas, two oratorios, countless songs and chamber works. Her music wove the atonal sound of Schoenberg with Irish folk melodies and the polyphony of JS Bach.

Sadly, there seems to be only a single recording of her work available here on CD – Frauentöne Vol. I (Orchesterwerke): Thorofon Classics – CTH 2259.