It may be helpful, before we explore this topic further, just to establish what is under examination.

When referring to a diminished or half-diminished something in music, we are referring to certain types of chords. We are also by implication, also talking about their harmonic function.

Chords in music consist of three or more notes that sound together. For a simple example, the chord of G major would be made up of the following notes; G, B and D.

The chord of G minor in contrast comprises the following notes; G, B flat and D. Major and minor chords are most commonly used in tonal music (music written in a given key). This is only the tip of the harmonic iceberg.

Alongside major and minor chords, music regularly incorporates more exotic variations. These can be extensions of the major and minor chords such as the 7th, 9th, 11th and 13th, or chords that don’t directly align with a key.

This type of chord can subtly colour a piece of music. Consider works by Ravel, Debussy or notable jazz exponents such as Bill Evans.

Included in the more exotic range of chords are the diminished and half-diminished varieties.

Diminished vs Half-Diminished

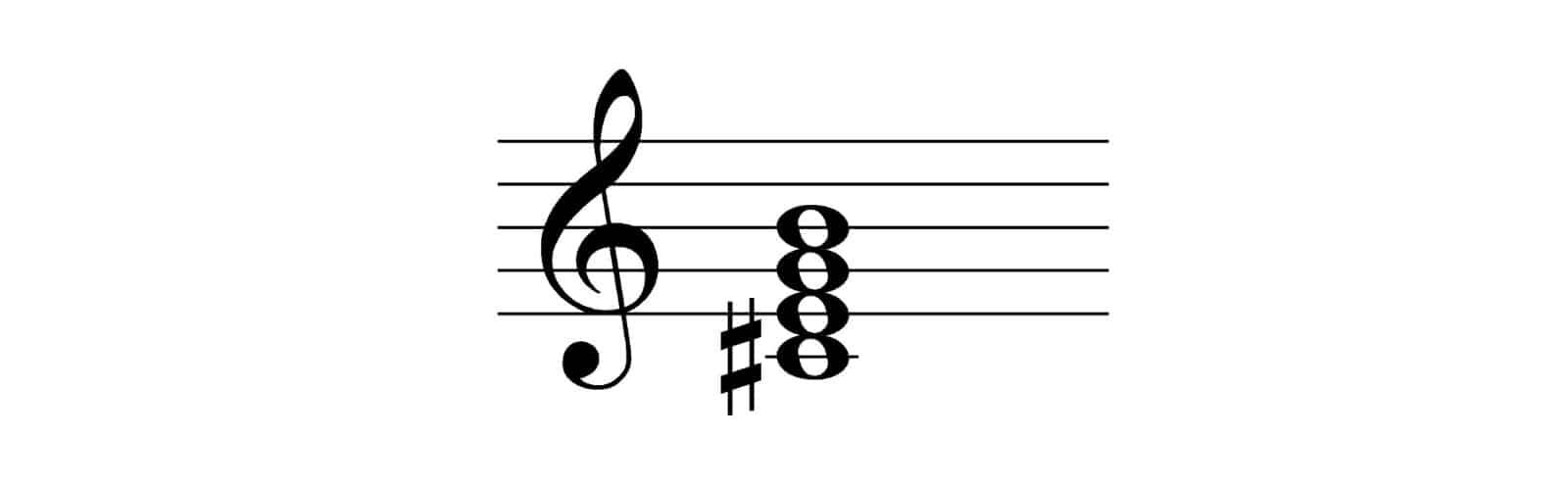

Let’s look more closely at the diminished chord. The illustration here is an example of a diminished 7th chord.

This title alone can provoke a furrowed brow as there appears not to be a 7th in this chord at all. The interval (distance between two notes), of a 7th, can be major or minor. Taking G as a root note, we could have a major 7th (G – F#) or a minor 7th, (G – F).

What happens with the diminished 7th is that the major 7th is diminished (reduced, or shrunk) by two semitones, or one tone if you prefer. This takes the F# down to an E.

To complete the analysis, let’s account for the other notes of this chord. Again taking G as the root note, we move a minor 3d upward to the Bb, a diminished 5th for the next (or augmented 4th), and finally the diminished 7th.

The result is a four-note chord essentially made up of minor thirds. Like other chords, the diminished 7th can be written in inversions too.

This means in the first inversion the G moves to the top of the chord; second inversion, the Bb moves to the top and third inversion the C# (Db), takes the top position. The intervallic relationship remains the same.

Its harmonic function is quite a complex one. Some refer to the diminished 7th as a pivot chord that allows modulation(change of key)to freely take place without the need for additional harmonic preparation. This makes the chord extremely useful for composers.

It can achieve this as it does not directly associate or link to a given key, meaning you can add it almost anywhere in a tonal piece and move the harmony in a new direction. (Clearly, the proper use of the diminished 7th requires careful consideration to be effective).

Pure functionality is not the whole story. The diminished 7th can bring an incredibly dramatic effect to a piece of music because it is not related to a key. It disturbs the harmonic flow, throwing the ear off the scent for long enough to destabilise the harmonic centre.

Many composers have used this to great effect in their music. Consider, as one example, the Finale to Mozart‘s 40th Symphony. At this point, Mozart seems to halt the bravado and swerve into a darker mood. It is his clever use of the diminished chord that makes this successful.

Turning our attention towards the other chord in the title, the half-diminished, let’s explore its finer details. Sometimes this chord is called the half-diminished seventh chord.

Perhaps this brings a little more clarity. This chord is remarkably similar to its cousin, the diminished 7th, but with key distinctions.

The first three notes are identical remembering that D flat is for the purpose of this discussion, the same as C# shown in the first illustration. Where the difference comes in the 7th.

In the half-diminished chord, the 7th (taking G as the root), is a minor one. This makes the resulting note an F, not an E.

At sight alone, it is understandable to think that there is not a significant difference between these two chords. Remarkably, however, when you hear them, one after the other, the distinction becomes immediately apparent.

I find that the diminished 7th has an instant and arresting sonority that pulls the harmonic rug from under you often leaving a feeling of anxiousness or uncertainty.

Here is a clip from Dudley-Do-Right that illustrates my point; albeit in a slightly comic fashion.

What you have here is the dastardly villain about to tie the helpless heroine to the train tracks accompanied by a series of diminished 7ths. This highlights and emphasises the tension perfectly.

The half-diminished chord (Gm7b5) as it’s often written, contrasts considerably. Many examples of the half-diminished chord exist in different genres of music. One that often stands out is in Wagner’s opening to his epic opera Tristan and Isolde.

What became known as the Tristan chord played during the opening bars, is an innovatively orchestrated half-diminished chord. Beyond pure function, it is how Wagner uses this chord to create such heightened emotional responses that are astonishing.

Music relies on tension and resolution. Wagner uses this chord and its subsequent repetitions to create only unresolved, aching tension and in so doing pushed the boundaries of tonality to their absolute limits.

With Wagner firmly in the ear, it is maybe easier to separate the qualities of the diminished and half-diminished chords.

Whereas the diminished 7th allows free harmonic movement within a composition and can provide moments of suspension and tension, the half-diminished chord offers another dimension completely.

It is an ambiguous chord even though its harmonic association is perhaps closer than that of the diminished 7th, but it promotes a deeper yearning (to my ears) and a very distinct sonority.

It is often a defining harmonic aspect of many jazz pieces as well as those from the classical world. There is no winner, simply two related but vitally different chords that open a universe of harmonic opportunities