Characteristics of Hector Berlioz Music

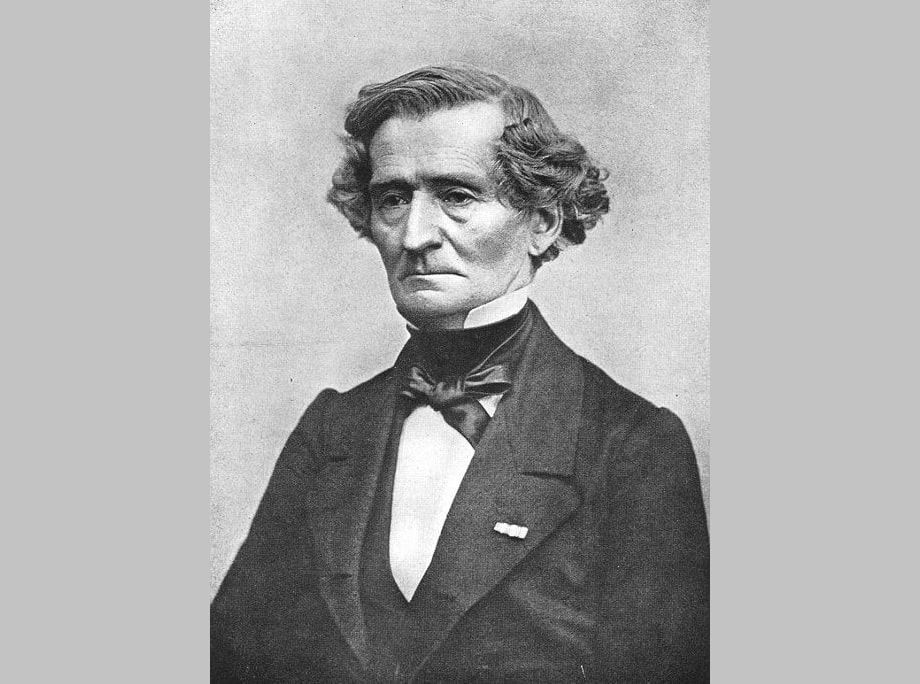

For many listeners, Hector Berlioz epitomizes the image of the Romantic composer. His works are often monumental in their ambitions and scale as well as their emotional outpourings. From the ‘Symphonie Fantastique’ to the ‘Les Troyens’, Berlioz was not a composer to do things by halves. Berlioz was a man of extreme passion and powerful vision with an extraordinary ability to convey this through his chosen medium of music.

We often tend to imagine that Berlioz, like many other composers of the past, as simply becoming successful through their abilities and strength of personality. This could not be further from the truth. Berlioz was not earmarked for musical fame. Far from it, Berlioz had been steered carefully into a career as a doctor by his determined Father who enrolled the young composer into the School of Medicine in Paris. Whilst the intentions of his Father were sensible and honorable, Berlioz had no interest in pursuing a career in medicine, instead, he had his eyes set on becoming a composer, and living in Paris was a fine place to start.

Berlioz up until this point was largely a self-taught composer. It is my impression that these early, self-reliant years gave rise to Berlioz’s unique approach to composition and in particular orchestration. Medicine was abandoned by Berlioz who devoted his time to studying composition and making regular visits to the Paris Opera where he found an affinity with the works of Gluck. The drama and narrative he adored in the operas soaked in through Berlioz’s skin and laid the groundwork for many future works.

In the early part of the 1820s Berlioz was able to have lessons with a leading professor at the Paris Conservatoire; Jean-François Lesueur under whose guidance Berlioz gained the necessary skills and discipline to eventually win the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1830 with his cantata titled ‘Sardanapale’. Berlioz had made four attempts in total to win the prize, so it is surprising to learn that he felt the cantata not to be one of his finest works and did his best to destroy the score.

What flowed from Berlioz’s pen next was the composition that marked him out as a musical revolutionary, his electric orchestral composition, ‘Symphonie Fantastique’ (1830). To put this composition into a little musical context, Beethoven had died only three years earlier, Chopin had completed his First Piano Concerto and Felix Mendelssohn had finished writing his Fifth Symphony (‘Reformation’).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VvZn3ULCRdg

Not only was this piece ambitious in length but it was also revolutionary in approach. Berlioz’s orchestration matched his compositional vision. The forces Berlioz employs are impressively grand but it is how he treats the orchestra that makes Berlioz stand out from composers of his time. Often Berlioz orchestrated using unusual combinations of instruments that create the colors and sonorities he needed to carry his vivid imagery. In 1843, Berlioz published his ‘Treatise on Instrumentation’ in which he explores and explains his ideas behind his orchestrations.

Perhaps more importantly, Berlioz used a musical device in the Symphonie Fantastique that became a hallmark of his compositional style; the ‘ideé fixe’. What this device does is thread its way through the entire composition, acting as a unifying idea, but as is appears in each movement, it transforms to match the narrative, mood or moment. In the Symphonie Fantastique, the ‘ideé fixe’ represents the dearly beloved, or apple of the protagonist’s eye but also the woman Berlioz idolized in real life. The actress Harriet Smithson was the lady in question, who after nearly seven years of courting eventually consented to become Berlioz’s wife. It is a deeply personal work that singles Berlioz out amongst his contemporaries.

The title of ‘symphonie’ is an extension of how Beethoven or Mendelssohn would have viewed a symphony, in as much as it is fully programmatic. That is to say, Berlioz based the composition on a structure originating from a narrative. (In this case the story of a doomed and love-struck artist). This moves the symphonic model of the late Classical and early Romantic composers into a completely different league. By using a programmatic approach to the symphonic work, Berlioz had opened the doors to a new understanding of what a symphony could be.

You might imagine that after composing such a monumental and uncompromisingly forward-looking work that the future for Berlioz was guaranteed. As it turns out, Berlioz did not find fortune and continued fame. The renowned virtuoso violinist Paganini, having been sufficiently impressed by the Symphonie Fantastique, asked Berlioz to write him a challenging piece for his newly acquired Stradivarius viola. Unfortunately, Berlioz felt unable to match the phenomenal technique that Paganini possessed in a piece of music, instead he composed Harold In Italy which merely featured the viola. Paganini was not impressed and refused to perform the piece.

In the light of an impending financial crisis, Berlioz took to journalism with a focus on music criticism. This he continued for the remainder of his life, and give a useful insight into Berlioz’s thoughts on many composers. Berlioz wrote kindly about Beethoven and had a passion for the operas of Carl Maria von Weber and Gluck. Berlioz was less kind with his writing about the incompetent violin and viola players and the counterpoint that dominated Baroque composers’ works.

Failure and disappointment dogged Berlioz throughout the decade. His enthusiastic adventure into opera, with the clear intention of reviving French Opera in the way he felt it should be represented, was not successful. ‘Benvenuto Cellini’ (1837) made too many demands of the singers, the staging, and the orchestra to the extent that the reception during the first performances was decidedly unfavorable.

With extended tours and concert programs, Berlioz was still struggling to balance the books. In 1846 his ‘Damnation of Faust’ was premiered but the Parisian audience seemed unable to or unwilling to appreciate Berlioz’s deeply romantic ideologies.

Towards the end of his life, Berlioz wrote the most extraordinary and perhaps most innovative large-scale composition; ‘Les Troyens’, (1858). For many, this is the jewel in the compositional crown of Berlioz. In this enormous work, we see the familiar traits of beautifully illustrative composition that refuses to be confined by any musical conventions. Here phrases are uneven, harmonies are unexpected, sometimes awkward and his orchestration bold and obdurate. This juxtaposed by sublime, passionate melodic writing that captures the spirit of one of Frances’ greatest composers.