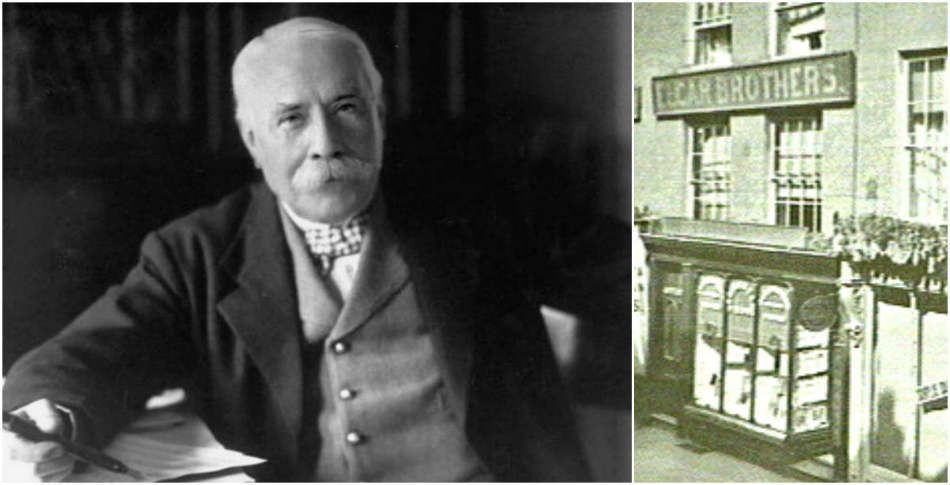

It was a music shop at 10 High Street in Worcester: “Elgar Bros. Pianoforte & Music Warehouse.” It was in this shop that young Edward Elgar discovered a vast array of classical music scores. It was from this shop that Edward borrowed a violin for independent study. It was at this shop that Edward decided to apprentice after an ill-fated stint in law. And it was because of this shop that Edward felt he was “kept out of everything decent” until he “made a name” for himself.

Born June 2, 1857, Edward was an attentive, enthusiastic youth, according to Jerrold Northrop Moore’s biography, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life. He played violin in the Crown Hotel Glee Club, organ in St. George’s Church, and bells in St. Helen’s Church. Technically, the last was only meant to signal curfew and the day of the month but, in Edward’s hands, things could become a bit more elaborate. “I used to prolong the ringing from three minutes to ten minutes,” Edward recalled, “Until the people in the neighbourhood complained, when I had to reduce the time.” Accordingly, Edward’s early twenties were full of hope. He had diligently saved enough money for a few violin lessons with Adolphe Pollitzer in London and made the most of them. Though unable to stay in the big city, the experience was heartening; Pollitzer had developed a favourable opinion of the young musician. In 1883, Edward spent a particularly blissful summer celebrating his engagement to Helen Weaver, the daughter of a shoe merchant on High Street.

The year 1884, however, ushered in a period of profound disappointment and unhappiness. In January, Edward wrote to a friend, “I have no money not a cent. And I am sorry to say have no prospects of getting any.” In July of that year, he dove headlong into despair: “I will not worry you with particulars but must tell you that things have not prospered with me this year at all, my prospects are worse than ever and to crown my miseries my engagement is broken off and I am lonely.” If anyone wondered whether the “quarter-life crisis” originated with millennials, poor Edward Elgar’s correspondence during this period should dispel that notion. In January 1886, he wrote, “I am very lazy now I have nothing to do I am not doing it.” Of course, this was not quite true. In addition to teaching violin all around Worcester, Edward had accepted an official position with St. George’s Church: “I am a full-fledged organist now and I hate it.”

Thankfully, Edward’s teaching brought him in contact with Miss Caroline Alice Roberts. Daughter of the late Major-General Sir Henry Roberts, Miss Roberts became enamoured with Edward and his music. They were engaged in September 1888. He was thirty-one. She was just shy of her fortieth birthday. Age, however, was the least of their worries. Her family vehemently opposed the marriage. Later, Edward and Alice’s daughter, Carice, recounted the furor: “They said he was an unknown musician; his family was in trade; and anyway he looked too delicate to live any length of time.” The Dowager Countess of Grantham could hardly have made more cutting remarks.

This engagement, despite all objections, made it to the altar. Alice agreed to a Catholic ceremony (though her family was devoted to the Church of England). The Elgars were married on May 8, 1889 with few present beyond the priest and witnesses for the register. The newlyweds moved to London. Edward’s career as a composer remained in doubt. Alice, already cut from the will of one aunt and shunned by many of her former intimates, knew further sacrifices had to be made. A diary entry in March 1890 notes that they had to sell Alice’s pearls to a pawn shop. Moore describes this as “the first of several such visits.”

Edward’s thirties involved a hard but steady climb towards recognition as a composer. The Elgars moved from London to Malvern to reduce their financial burden. Edward taught violin at a girls’ school run by Miss Rosa Burley, a young woman who would become a good friend. Once, at a concert featuring Edward’s Spanish Serenade, Miss Burley overheard a conversation between the two ladies behind her:

“[They] seemed less interested in the music than in its composer. What appeared to strike them as remarkable, however, was not that he could write music, but that he had married a member of their own social circle… They did not wish to cut Alice Roberts though apparently a good many of them had done so but they naturally felt that they could not be expected to meet a man whose father kept a wretched little shop in Worcester and even tuned their pianos. It was all most awkward.”

With Alice’s steady encouragement, Edward continued to compose around his teaching commitments. He also took up golf, although this too could be a source of awkwardness. None of his fellow golfers needed to take such mundane commitments as teaching into consideration when scheduling a foursome.

The year of Edward’s forty-second birthday brought great acclaim for his ‘Enigma’ Variations. Not long after, Musical Times wrote a profile piece on the man increasingly viewed as the greatest English composer since Purcell. They submitted the article to the Elgars for final approval. Alice replied with a few requests, chiefly the following: “as E. has nothing to do with the business in Worcester […] would you please leave out details which do not affect him and with which he has nothing to do – His interests being quite unconnected with business.” Edward was less diplomatic: “Now – as to the whole ‘shop’ episode - I don’t care a d–n! I know it has ruined me and made life impossible until I what you call made a name - I only know I was kept out of everything decent, ‘cos ‘his father keeps a shop’ - … but to please my wife do what she wishes.” Musical Times obliged.

A famous anecdote endures from Edward’s childhood when this son of a piano tuner was asked his name on his first day at a new school. “Edward Elgar,” the boy said. The schoolmaster tried to remind the child to address his superiors with respect. “Say, ‘Sir,’” he prompted. To which the boy quickly responded, “Sir Edward Elgar.” Nearly four decades later, “Sir” would indeed be the proper address for Edward Elgar. He was knighted on July 5, 1904. He would never again be dismissed by high society on the basis of a shop at 10 High Street, Worcester.