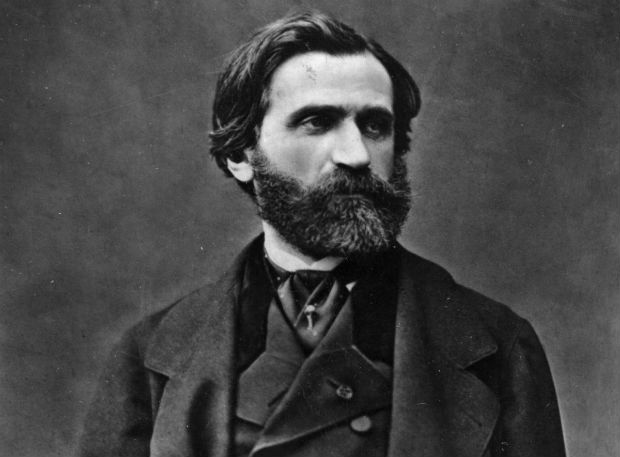

In The Man Verdi, Frank Walker describes Giuseppe Verdi‘s birthplace as “the merest hamlet”. Born in Le Roncole on October 10, 1813, Giuseppe Verdi was the son of an inn-keeper in a land of peasantry. At age ten, he began attending school in the larger town of Busseto and boarding with a friend of his father’s, a cobbler. On Sundays and feast days, he would trek back to Le Roncole to play the organ for services. It was a three mile journey each way and, according to his second wife (Giuseppina Strepponi), he would often walk barefoot, carrying his shoes to preserve the leather.

During his time in Busseto, Verdi began serious musical study under Ferdinando Provesi, a well-respected figure in town. News of Verdi’s talent reached the ears of Antonio Barezzi. Barezzi owned a popular store on the main street of town. According to Walker, “There he sold wine, groceries and liqueurs of his own distillation.” Barezzi was an enthusiastic music lover - a “maniaco dilettante,” in local renown. He also had four daughters.

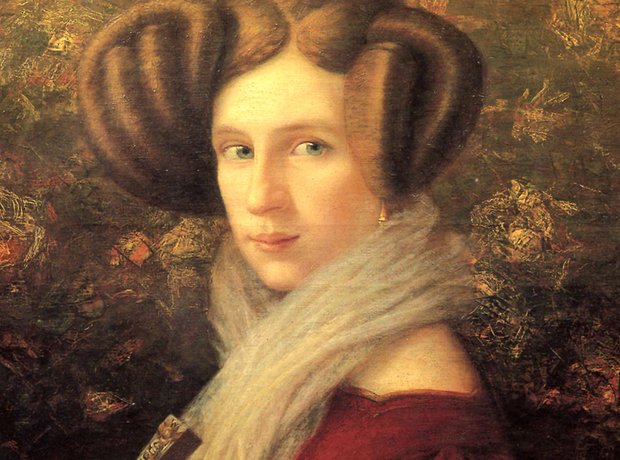

As Verdi began spending more time at the Barezzi house, he grew close to the eldest daughter, Margherita. Born May 4, 1814, Margherita took singing and piano lessons from Verdi, who moved from the cobbler’s lodgings to the Barezzi house full time as of May 1831. When Barezzi discovered from his wife that his daughter and the aspiring musician were in love, he became more invested in Verdi’s career.

Recognizing that Busseto offered limited opportunities for Verdi to further his education, Barezzi assisted him in applying for a grant from the Monte di Pietà e d’Abbondanza to study at the Conservatory in Milan. Although it was agreed that Verdi would receive the first available pension in their funds, the money was almost two years away. In the meantime, Barezzi would financially support his future son-in-law. Verdi went to Milan, set up in temporary lodgings with a friend of Barezzi’s. He applied to the Conservatory, sat the examination, and was rejected.

The news of Verdi’s failure surprised Busseto but must have devastated Barezzi. If Verdi was to stay in Milan and study privately, his expenses would undoubtedly double. But Barezzi considered the cost an investment. As it turned out, the Conservatory’s decision was based more on technicalities than talent. At eighteen, Verdi was considered too old for the regular application process and needed to apply for a special exemption. This, on top of his foreignness and the opinion of a pianoforte teacher that his incorrect hand positioning would be too difficult to correct at such an advanced age, led to the (now infamous) rejection.

As Verdi was completing his studies in Milan, Provesi died and Busseto erupted into a cultural war over who should replace him in his official posts. While one side staunchly supported Verdi, the man himself, disenchanted by the provincial politics of Busseto, applied to be Maestro di Cappella and organist to the cathedral of Monza. Word of this application did not please his “supporters.” In a letter to his Milan teacher, Verdi wrote, “If my benefactor Barezzi would not have had to suffer on my account the almost general hostility of the district I should have left straight away.”

Though Margherita’s letters with Verdi are lost, she is quoted in a letter from a third party to her father during this time, asserting a desire for Verdi to remain in Milan: “Verdi will never, never settle at Busseto. First of all because, having devoted himself to music for the theatre, he looks for success in that and not in church music [.…] In the last analysis, any advantageous commission he has obtained would be invalidated and all his patrons let down.” Nevertheless, Milan would have to wait. Verdi accepted the position of Maestro di Musica in Busseto.

Things moved quickly both personally and professionally from there. Margherita and Giuseppe were officially engaged on April 16, 1836. Verdi signed his contract with Busseto on April 20. He married Margherita on her birthday two weeks later. On March 26, 1837, they welcomed their first child: a girl, Virginia. In early May 1838, with Margherita expecting their second child, Verdi travelled to Milan alone to meet with Bartolomeo Merelli, the impresario of La Scala. On July 11, 1838, Margherita gave birth to a son, Icilio. In the two years following this moment, Verdi would lose his daughter, premiere a successful opera at La Scala, then bury his son and his wife while trying to write a comic follow-up.

Un giorno di regno failed spectacularly at its premiere on September 5, 1840. In response, Merelli yanked its successive performances and replaced them with Verdi’s previous effort, Oberto. Though Verdi was still under contract with La Scala, he did not see how he could fulfill his obligations. After resigning his position in Busseto, he had moved to Milan with a young family and a promising career. Now, at age twenty-six, his home was full of ghosts. In Verdi’s words, “Un giorno di regno failed to please: certainly the music was partly to blame, but partly too, the performance. With mind tormented by my domestic misfortunes, embittered by the failure of my work, I was convinced that I could find no consolation in my art and decided never to compose again.”

Margherita does not loom large in Verdi’s biographies. Her father, Barezzi, remains a strong presence in Verdi’s life until his death in 1867 but Verdi’s first wife abruptly disappears after this fateful low point in 1840. Perhaps fittingly, even the cause of her death remains a mystery. Barezzi only describes it as “a disease, perhaps unknown to doctors.” To biographers, she is an enigma but to Verdi, she was an intimate. The impact of her loss, the loss of a woman he had known and loved from childhood, compounded by the loss of their two children, cannot be understated.

Of course, Verdi would compose again. His first great opera, Nabucco, premiered at La Scala on March 9, 1842. The apocryphal story of its conception goes thusly: Verdi reluctantly accepted a libretto from Merelli and threw it down on his table one day, catching the phrase “Va, pensiero, sull’ ali dorate” from the open page. Ultimately, whether this story is true or not, the libretto should not be credited as Verdi’s awakening. It was merely his outlet. It offered the possibility of cathartic expression to an anguished soul. The agony that gave his music its ecstasy was not found in a book. It came in large part from the brewer’s daughter.